Women's Health Pioneers

How Female Scientists Changed Medicine Forever

While researching "The Art of Female Health," I kept running into the same infuriating pattern: groundbreaking discoveries about women's bodies, made by brilliant female scientists, that were either ignored, attributed to male colleagues, or buried in obscure journals for decades.

There's this pervasive myth that women's health science is somehow "new"—that we're only now starting to understand female biology because, you know, women just started doing science or something. Bullshit. Women have been doing revolutionary research on women's health for over a century. The problem wasn't lack of knowledge. The problem was that nobody was listening.

So let's talk about the women who changed medicine forever, often without recognition, credit, or even basic acknowledgment. The ones who proved that female bodies aren't just "smaller male bodies with hormones." The ones who discovered fundamental biological processes while being excluded from the very institutions they were advancing.

Because as we approach International Women's Day and the release of "The Art of Female Health," it's time to recognize that the science of female health has always been here. We've just been systematically prevented from accessing it.

Rosalind Franklin: The DNA Discovery They Tried to Erase

Let's start with the obvious one that still makes me rage. Rosalind Franklin discovered the double helix structure of DNA. Not Watson and Crick. Franklin. Using X-ray crystallography, she captured Photo 51—the image that revealed DNA's structure—and her research was literally stolen by her male colleagues [1].

Watson and Crick saw her unpublished data without her permission or knowledge, used her findings to build their model, and won the Nobel Prize. Franklin died at 37 from ovarian cancer, likely caused by radiation exposure from her research, before the prize was awarded. She received no credit in their Nobel acceptance speech.

But here's what's rarely discussed: Franklin's work went far beyond DNA structure. She did pioneering research on viruses and coal, and her methodological rigor set standards that are still used today. She proved that women could do cutting-edge structural biology at the highest level, even while being actively sabotaged by her colleagues.

The erasure of Franklin's contributions isn't just historical injustice—it's emblematic of how women's scientific work, especially work related to reproduction and biology, has been systematically minimized or attributed to men.

Dr. Helen Brooke Taussig: The Mother of Pediatric Cardiology

Helen Brooke Taussig was partially deaf and dyslexic in an era when those conditions were considered incompatible with medical practice. She became one of the most important cardiologists of the 20th century, pioneering the field of pediatric cardiology and developing the first successful surgical treatment for "blue baby syndrome" [2].

But her most significant contribution to women's health? She led the fight to keep thalidomide out of the United States. While thousands of European babies were born with severe birth defects because their mothers took thalidomide during pregnancy, Taussig investigated the drug, recognized the pattern, and campaigned relentlessly to prevent FDA approval in the US.

Her testimony before Congress directly led to stricter drug safety regulations and fundamentally changed how medications are tested for effects on pregnancy. She saved countless lives and established the principle that drugs need to be tested on women, not just extrapolated from male-only studies.

Taussig did all this while facing constant discrimination as a woman in medicine, being denied admission to multiple medical schools, and being told repeatedly that women lacked the "temperament" for surgery.

Dr. Virginia Apgar: Beyond the Apgar Score

Everyone knows the Apgar score—the assessment of newborn health performed one and five minutes after birth. What most people don't know is that Virginia Apgar revolutionized newborn care, anesthesiology, and birth defect research, all while being denied opportunities because of her gender.

Apgar wanted to be a surgeon but was told that surgery wasn't appropriate for women. She pivoted to anesthesiology and became the first woman to head a division at Columbia University. Her systematic approach to newborn assessment transformed outcomes and became the global standard [3].

But her work went further. She became a leader in the study of birth defects and genetic disorders, helped establish what would become the March of Dimes' birth defects program, and fundamentally changed how we think about congenital conditions and maternal health.

She did all this while maintaining that women belonged in every area of medicine and actively mentoring younger women entering the field. Her legacy isn't just the Apgar score—it's the precedent that women can establish entirely new medical fields.

Dr. Jane C. Wright: Cancer Research Pioneer

Jane Wright developed chemotherapy techniques that are still used today. She pioneered the use of methotrexate to treat breast cancer and skin cancer, developed innovative drug delivery methods, and was among the first physicians to test treatments on human tissue cultures rather than just animals.

As an African American woman in medicine in the 1940s-60s, she faced double discrimination. She became the highest-ranking African American woman in medical administration, founded the cancer chemotherapy department at NYU, and served as president of the New York Cancer Society.

Wright's work on individualized cancer treatment—testing which drugs would work on a patient's specific cancer before administering them—anticipated modern precision medicine by decades. She understood that cancer isn't one disease and that treatment needs to be personalized, a concept that mainstream medicine resisted for decades.

Her research directly impacts how we treat breast cancer today, yet most people have never heard her name. That's not an accident—it's systematic erasure of women's contributions, especially women of color.

Dr. Rita Levi-Montalcini: Neuroscience in Hiding

Rita Levi-Montalcini won the Nobel Prize for discovering nerve growth factor (NGF), a finding that revolutionized neuroscience and our understanding of how cells develop, regenerate, and die. But she did her initial research in her bedroom during World War II, hiding from fascist persecution as a Jewish woman in Italy.

She set up a makeshift laboratory in her home, using chicken eggs and basic equipment, and made discoveries that would later earn her the Nobel Prize. After the war, she continued her research and identified NGF's role in cell growth, cancer development, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Her work laid the foundation for understanding Alzheimer's disease, cancer biology, and tissue regeneration. She lived to 103, attributing her longevity and mental acuity to continued intellectual engagement—living proof of her own neuroscience research about the importance of cognitive stimulation.

Levi-Montalcini did groundbreaking research despite facing antisemitism, sexism, and literal war. She proved that scientific genius doesn't require institutional support—though institutional barriers kept her and countless other women from achieving even more.

Dr. Rosalyn Yalow: Making the Invisible Visible

Rosalyn Yalow developed radioimmunoassay (RIA), a technique that allows detection of incredibly small amounts of substances in blood. This might sound technical and narrow, but it revolutionized endocrinology and women's health in profound ways.

RIA made it possible to accurately measure hormones in blood for the first time. Suddenly, we could diagnose thyroid disorders, measure insulin in diabetes, track reproductive hormones, and understand endocrine function with precision. Modern hormone testing—the foundation of understanding conditions like PCOS, thyroid disorders, and hormonal imbalances—exists because of Yalow's work.

She won the Nobel Prize in 1977, only the second woman to win in Physiology or Medicine. She did this while raising two children and facing constant discrimination in physics departments that refused to hire women. She was initially rejected from graduate school because she was a woman and only accepted after a spot opened when a male student was drafted.

Her response to winning the Nobel? She used the platform to advocate for women in science, explicitly stating that barriers to women in research hurt everyone by limiting the pool of talent addressing critical problems.

Dr. Gertrude Elion: Drug Development Revolutionary

Gertrude Elion never obtained a PhD because she couldn't afford to stop working to pursue one. She still won the Nobel Prize for developing drugs that treat leukemia, gout, malaria, and herpes, and for discovering principles of drug design that are still used today.

Her work on immunosuppressive drugs made organ transplantation possible. Her research on antiviral drugs laid groundwork for HIV treatments. She developed the first treatment for childhood leukemia that actually worked, transforming a uniformly fatal diagnosis into a survivable one.

Elion faced rejection after rejection from graduate programs and research positions because she was a woman. She took a position as a lab assistant—the only job available to her—and turned it into a career that would change medicine forever.

She specifically mentored young women scientists throughout her career, recognizing that the barriers she faced still existed and actively working to dismantle them. Her legacy isn't just the drugs she developed—it's the precedent that women belong in pharmaceutical research and drug development.

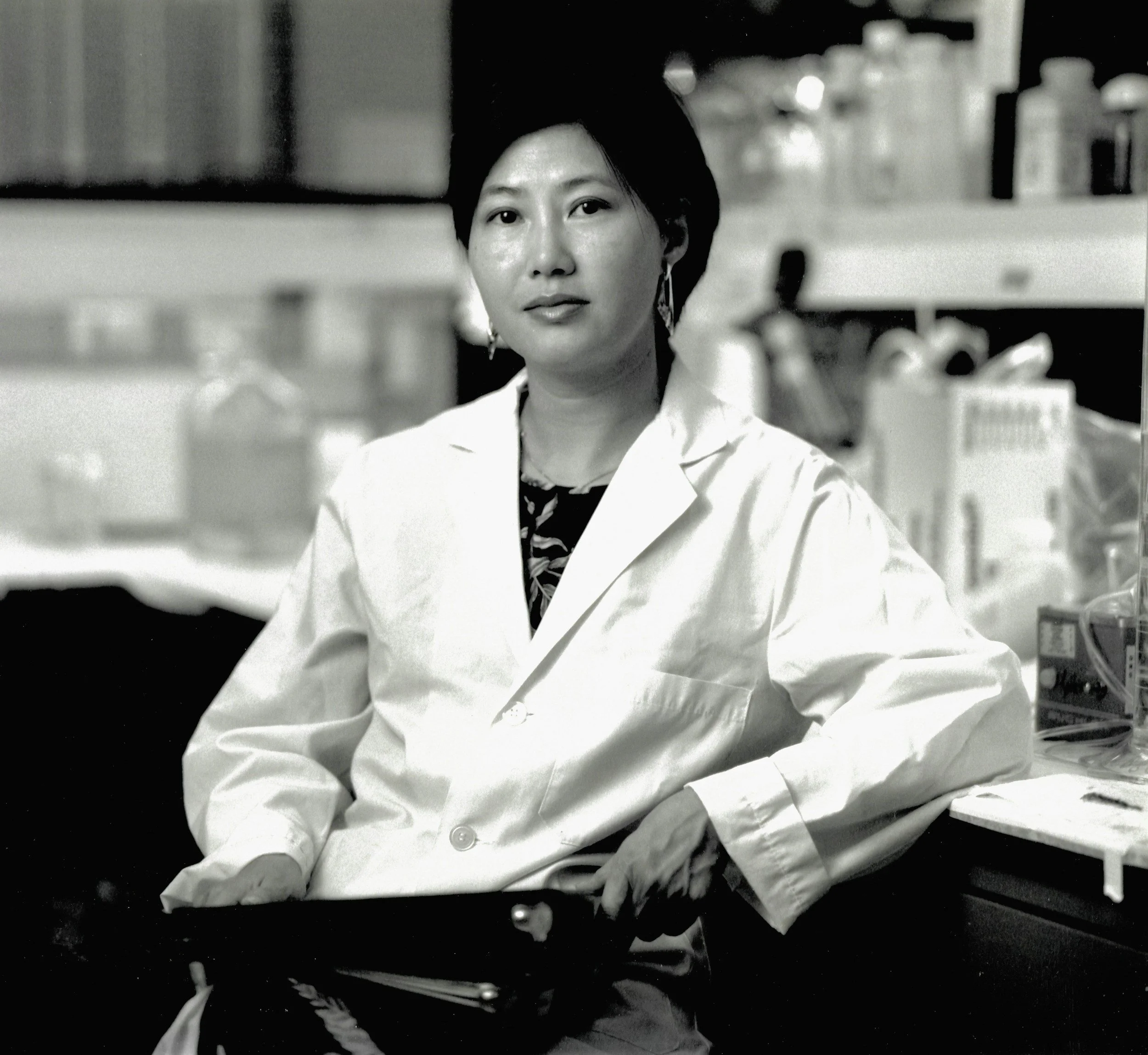

Dr. Flossie Wong-Staal: HIV Research Pioneer

Flossie Wong-Staal was the first scientist to clone HIV and determine its genetic structure, work that was essential for developing HIV tests and treatments. She identified the genes that allow HIV to replicate and attack immune cells, fundamentally advancing our understanding of how the virus works.

As a Chinese-American woman in virology, she faced assumptions that she was less capable, couldn't lead research teams, and should focus on "supporting" male colleagues. She became one of the world's leading HIV researchers, was nominated for the Nobel Prize multiple times, and was named the top woman scientist of the 20th century by The Institute for Scientific Information.

Her work directly led to drugs that transformed HIV from a death sentence to a manageable chronic condition. Every person living with HIV today benefits from Wong-Staal's research, yet her name remains relatively unknown outside specialized scientific circles.

Dr. Tu Youyou: Ancient Wisdom Meets Modern Science

Tu Youyou won the Nobel Prize for discovering artemisinin, the most effective treatment for malaria, which has saved millions of lives. She did this by systematically studying ancient Chinese medical texts, identifying promising compounds from traditional remedies, and rigorously testing them using modern scientific methods.

Her approach—combining traditional knowledge with contemporary research techniques—was revolutionary and controversial. Western scientists dismissed traditional medicine as unscientific; Chinese scientists were skeptical of returning to old texts. Tu did it anyway.

She tested substances on herself before enrolling patients in trials. She persisted through the Cultural Revolution when scientific research was considered suspect. She worked without recognition for decades before finally receiving the Nobel Prize in 2015.

Tu's work proves that women's ways of knowing—including attention to traditional practices, holistic approaches, and integration of different knowledge systems—can lead to breakthrough discoveries. Her research saved millions of lives and demonstrated that scientific progress doesn't require abandoning other forms of knowledge.

What They Had in Common (Besides Being Brilliant)

Every single one of these women faced institutional barriers designed to keep them out of science. They were rejected from programs, denied positions, paid less than male colleagues, had their work stolen or attributed to men, and were told repeatedly that women couldn't do serious research.

They persisted anyway. They did groundbreaking work from bedrooms, with limited resources, while raising children, while facing discrimination based on gender, race, religion, or disability. They made discoveries that saved millions of lives and established entirely new fields of research.

And they were systematically erased from history, their contributions minimized or attributed to male colleagues, their names forgotten while men won prizes for their work.

This isn't ancient history. Many of these patterns continue today. Women's health research is still underfunded. Women scientists still face discrimination and harassment. Research on female-specific conditions is still considered "niche" while male-focused research is considered universal.

Why This Matters for Your Health Today

The erasure of women's scientific contributions isn't just about fairness or historical accuracy. It directly affects your health right now.

When we don't recognize women's contributions to science, we reinforce the narrative that women's health is secondary, that female biology is less important, that research on women's bodies is less valuable. This leads to:

Continued underfunding of women's health research

Medical trials that exclude women or don't analyze sex-based differences

Treatments optimized for male bodies being prescribed to women

Conditions that primarily affect women being dismissed or undertreated

Women's symptoms being attributed to anxiety or hormones rather than investigated seriously

The women we've discussed didn't just advance science—they advanced women's health specifically. Franklin's work on DNA structure informs genetic research on female-specific conditions. Taussig changed drug safety regulations that protect pregnant women. Apgar transformed maternal and newborn care. Wright pioneered treatments for breast cancer. Yalow made hormone testing possible. Elion developed immunosuppressive drugs used in women's autoimmune conditions. Wong-Staal's HIV research addressed a disease that affects millions of women. Tu's malaria treatment saves pregnant women and children.

These discoveries happened because women were doing the research, often specifically addressing women's health needs that male researchers ignored.

The Art of Female Health: Standing on Their Shoulders

Writing "The Art of Female Health" meant reckoning with this history. Every chapter I wrote exists because these women—and countless others whose names we don't even know—did the foundational research that made understanding female biology possible.

They proved that women's bodies deserve rigorous scientific investigation. They demonstrated that sex-based differences in biology matter. They established that women's health isn't a subset of general health—it's a distinct field requiring specialized knowledge and research.

The book releases on International Women's Day because women's health science has always been intertwined with women's rights. Access to knowledge about our bodies is power. Understanding the biological processes that affect us is liberation. Having scientific evidence to counter dismissive medical treatment is necessary for survival.

"The Art of Female Health" synthesizes cutting-edge research on female biology—circadian rhythms, hormonal optimization, metabolic health, stress physiology, nutritional biochemistry—all built on foundations laid by women scientists who fought to make this knowledge exist.

It's a coffee table book because these women's legacies deserve to be visible, beautiful, and proudly displayed. It's a comprehensive guide because you deserve access to the science that women fought to create, often at great personal cost.

When you pre-order "The Art of Female Health" (available March 8th), you're not just getting information about your body. You're participating in a legacy of women creating and sharing knowledge about female health, despite every institutional barrier designed to prevent exactly that.

You're saying that women's health science matters. That our bodies deserve rigorous research. That the women who dedicated their lives to understanding female biology deserve recognition. That we refuse to accept medical systems built on research that excluded us.

The Next Generation of Pioneers

The women discussed here opened doors, but those doors haven't stayed open without effort. Every woman in science today still faces many of the same barriers—funding discrimination, sexual harassment, work-life balance pressures that don't equally affect male colleagues, and the assumption that women's research is less important.

But there's also momentum. More women are entering STEM fields. Women's health research is getting more attention (though still not enough funding). Sex-based differences in biology are being recognized as scientifically significant rather than inconvenient complications.

The next generation of discoveries about women's health will come from diverse women scientists who refuse to accept that female biology should be studied less rigorously than male biology. They'll build on the foundations laid by Franklin, Taussig, Apgar, Wright, Levi-Montalcini, Yalow, Elion, Wong-Staal, Tu, and thousands of others.

And hopefully, this time, we'll actually remember their names.

Because women's health pioneers didn't change medicine despite being women. They changed medicine because they were women—because they brought different perspectives, asked different questions, and refused to accept that female biology was too complicated or too niche to deserve serious scientific investigation.

Their legacy isn't just the discoveries they made. It's the proof that women's contributions to science are essential, that excluding women from research hurts everyone, and that the future of medicine requires centering women's experiences and biology rather than treating them as afterthoughts.

On International Women's Day, let's honor these women not just by remembering them, but by demanding better. Better funding for women's health research. Better representation of women in clinical trials. Better treatment when we seek medical care. Better access to information about our bodies.

"The Art of Female Health" is my contribution to that demand. Pre-order it now, and join the legacy of women who refuse to accept that our health is secondary, our biology is inconvenient, or our scientific contributions are erasable.

They changed medicine forever. Now it's our turn to make sure that change sticks.

References

[1] Maddox, B. (2002). Rosalind Franklin: The dark lady of DNA. HarperCollins Publishers.

[2] Neill, C. A., & Clark, E. B. (1994). Tetralogy of Fallot: The first 300 years. Texas Heart Institute Journal, 21(4), 272-279.

[3] Apgar, V. (1953). A proposal for a new method of evaluation of the newborn infant. Current Researches in Anesthesia & Analgesia, 32(4), 260-267.